(2004 – 2008)

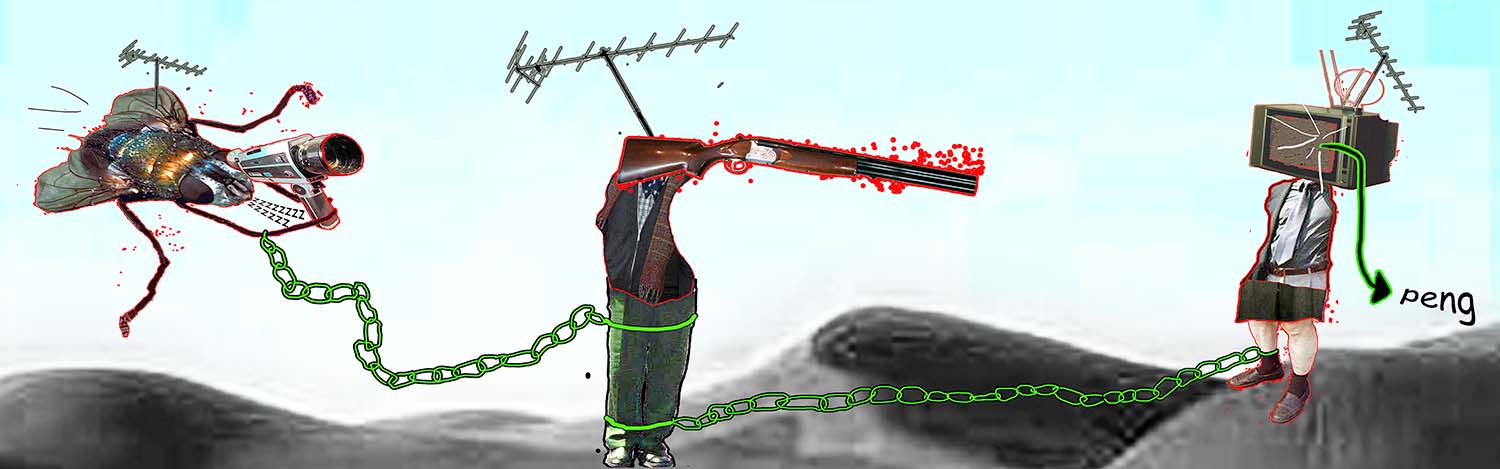

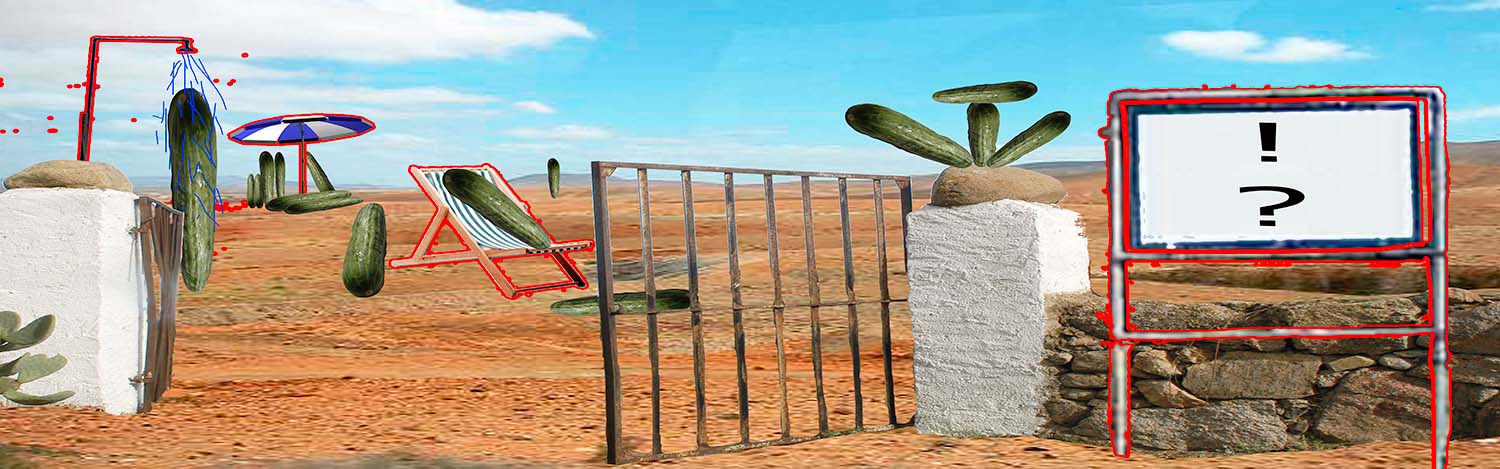

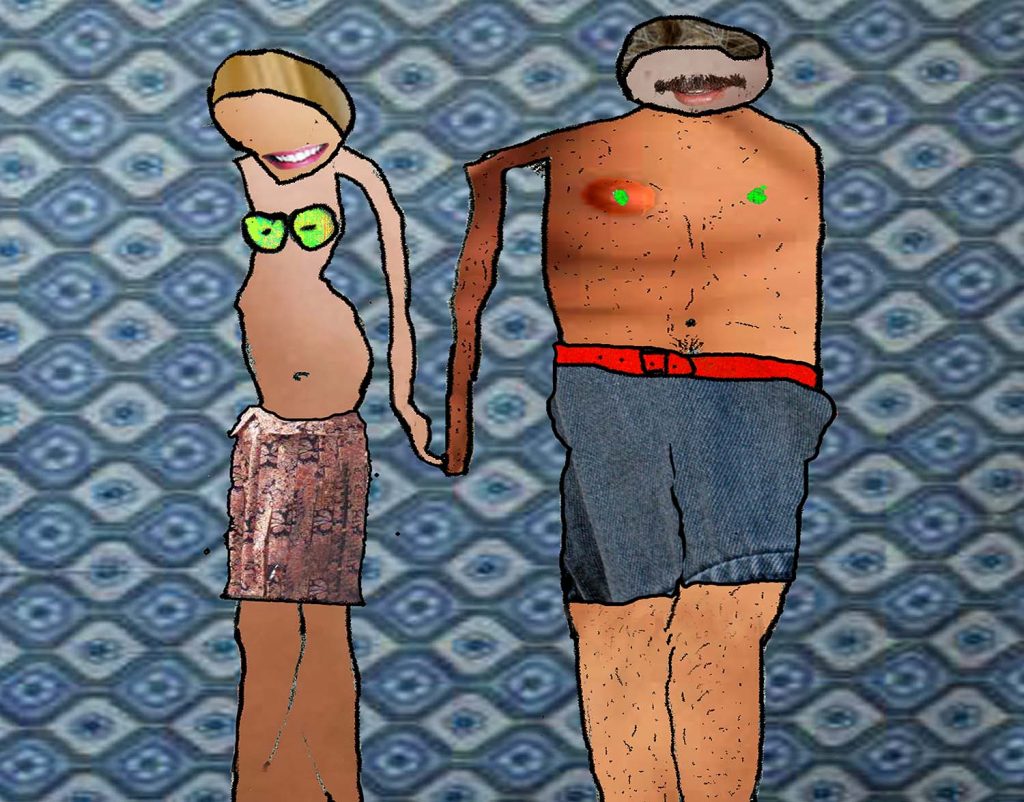

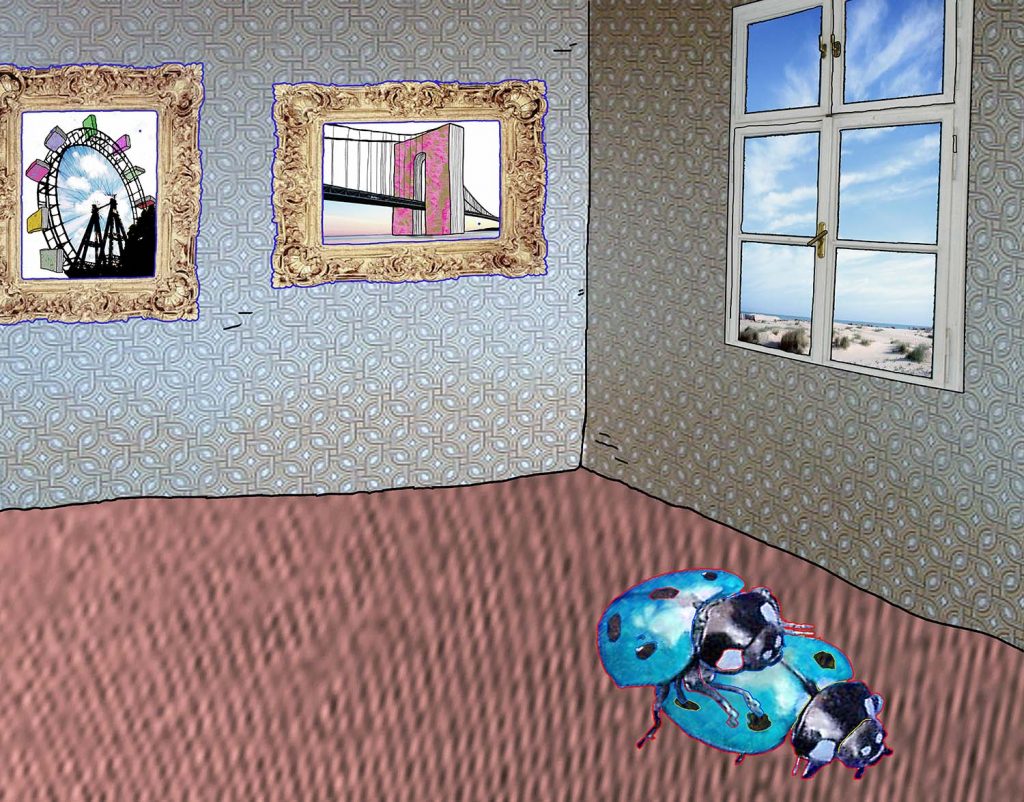

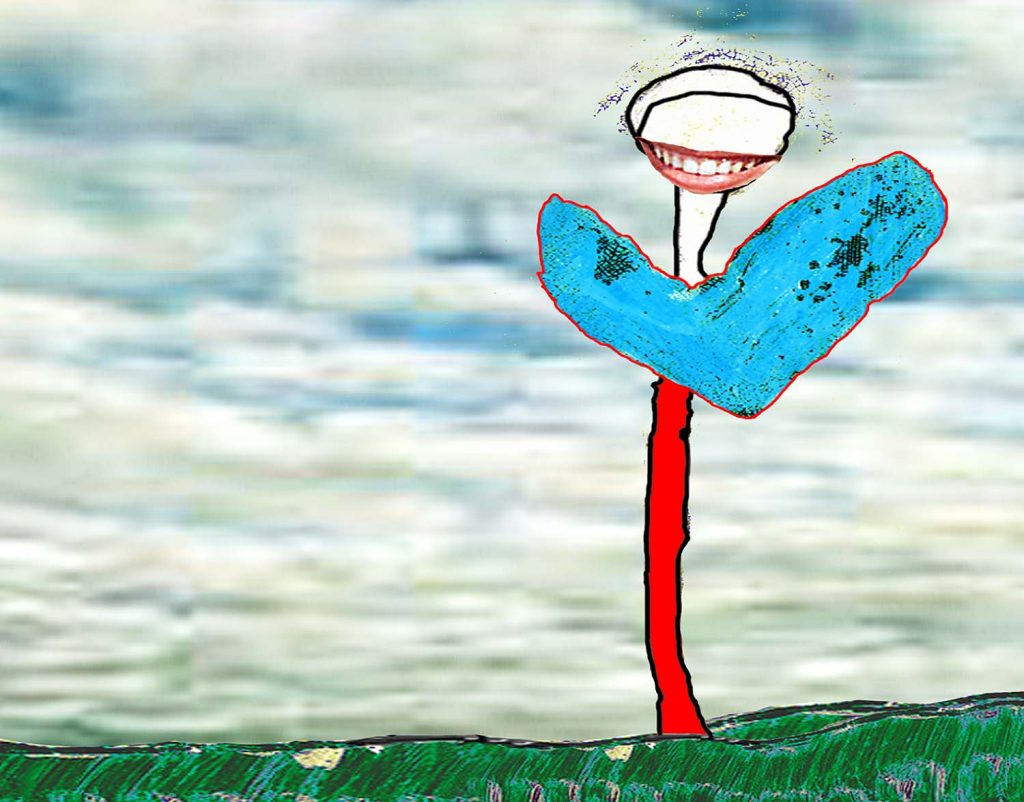

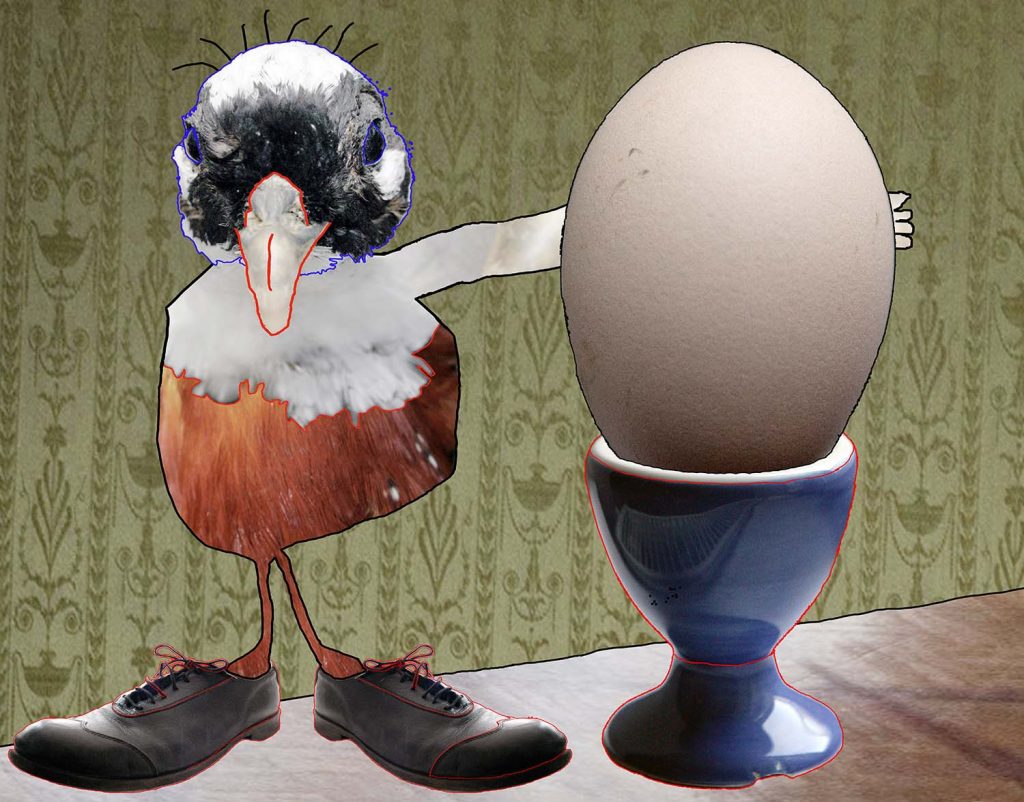

#01 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#02 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#03 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#04 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#05 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#06 50 x 160 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

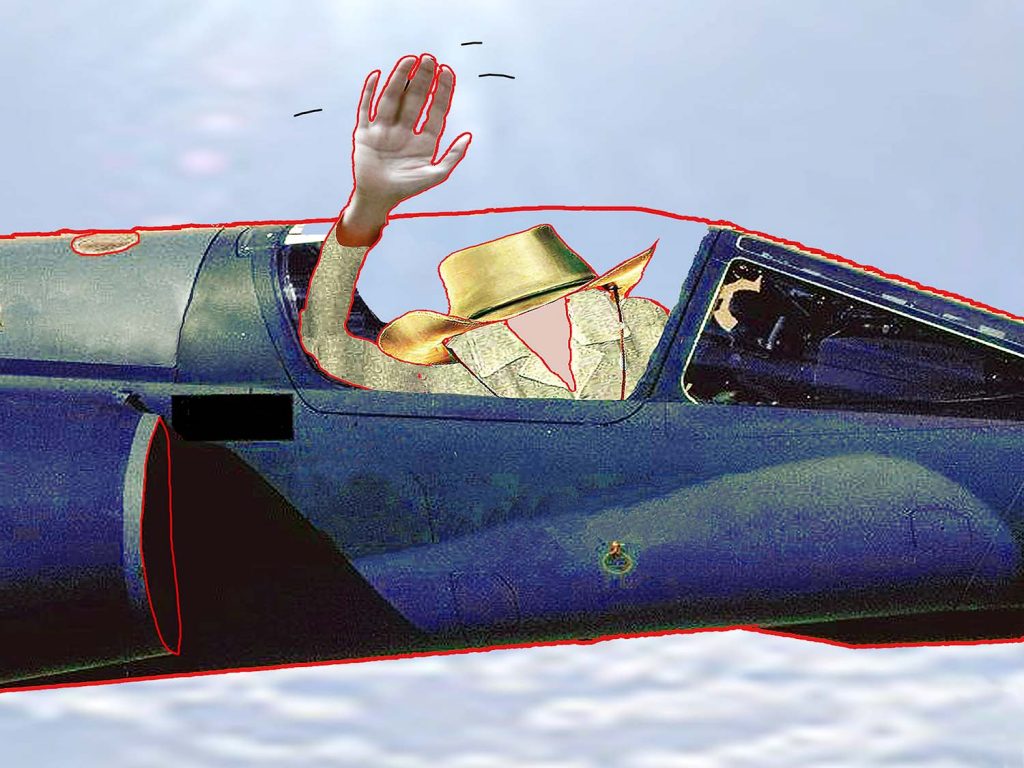

#07 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#08 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

# 09 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#10 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#11 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#12 50 x 70 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

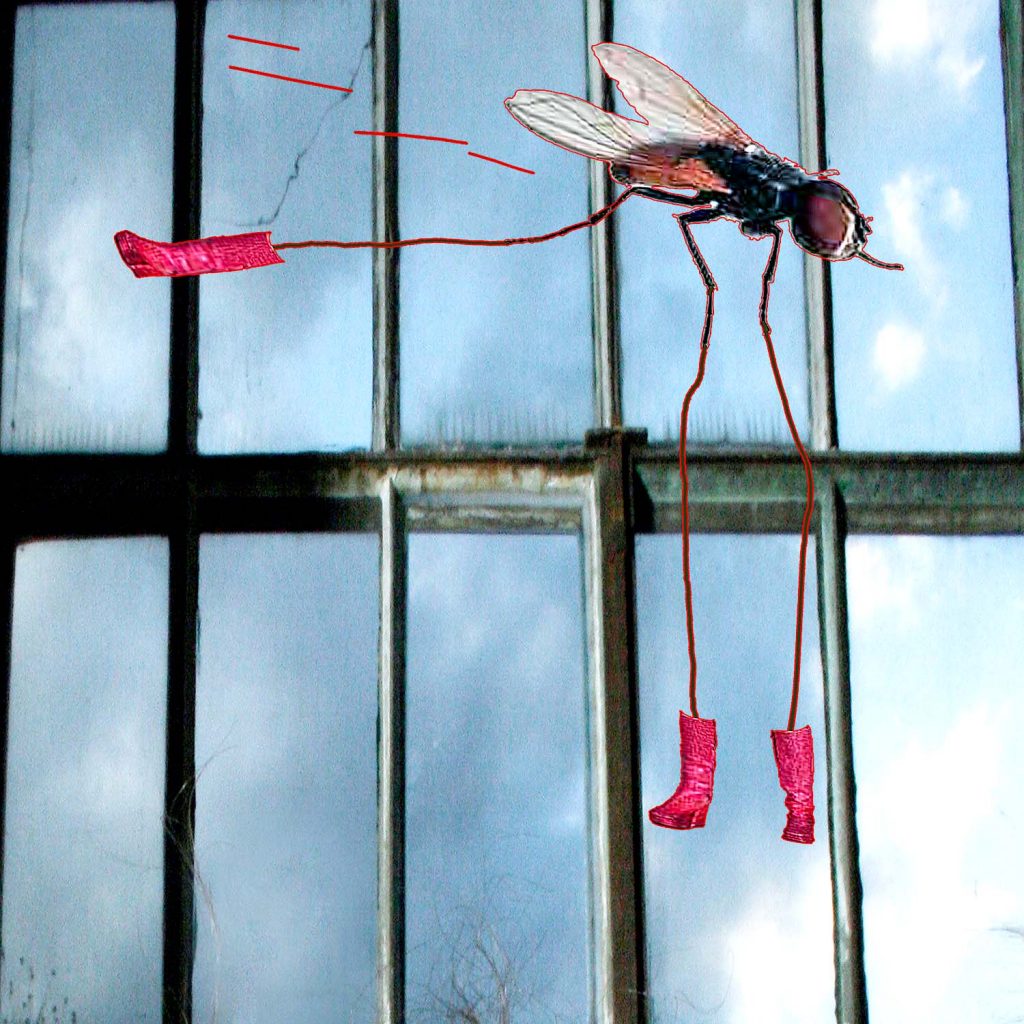

#13 50 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#14 50 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#15 50 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#16 50 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#17 50 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#18 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#19 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#20 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#21 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#22 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#23 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#24 47 x 60 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#25 60 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#26 60 x 50 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

#27 70 x 140 cm | C-Print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

Bildband | Book

Softcover | 96 pages | Size: 15 x 30 cm | Edition: 500 copies

ÖIP / Eikon Verlag, Austria, 2010 | ISBN: 978-3-902250-55-1

Book design by Doris Pesendorfer

Languages: German, English, French, Slovenian

Text by Meinhard Rauchensteiner

VON BILDERN UND TEXTEN – VON TEXTEN UND BILDERN

— Meinhard Rauchensteiner

Prima la musica, poi le parole – sagt man so leichthin. Und wenn’s nicht gerade Schuberts „Erlkönig“ ist, glaubt man’s auch gerne. Von der „Ode an die Freude“ schweigen wir, aber insgesamt stellt sich dann doch die Frage: Wie ist das mit Vertonungen? Schon das Wort legt nahe, dass doch der Text zuerst und die musica das Spätere ist. Ja, chronologisch vielleicht. Doch besitzt die Chronologie für ein Kunstwerk Bedeutung? Mittlerweile ist schließlich auch das Plagiat zur hysterisch bejubelten Kunstform erhoben worden, an der Verlage und Hegemanns gut verdienen. Wen kümmert da schon die altmodische Frage, ob die Henne oder das Ei zuerst da war?

Aber vielleicht ist es außerhalb Berlins nicht so dringend notwendig, das Kind mit dem Bade auszuschütten, und vielleicht lohnt es sich, die schnoddrige Wurschtigkeit bei der Beurteilung der Fotocartoons von Marko Lipuš, um den es ja – ich hab vergessen, das eingangs zu erwähnen (Teufel aber auch) – eigentlich geht, kurz beiseite zu lassen.

Diese Fotocartoons – es sind so ungefähr viele an der Zahl – erschienen von März bis Oktober 2007 allwöchentlich in der Wochenendbeilage Album der österreichischen Tageszeitung Der Standard. Zugrunde lag ihnen die Einladung des Autors an diverse Schriftsteller, einen Gedanken zu formulieren, zu dem in weiterer Folge Bilder produziert werden sollten. Folgerichtig war die Intervention dann auch übertitelt: „Der Gedanke“. Wohlgemerkt: im Singular. Nun ist das an sich schon spannend, denn Schriftsteller produzieren Geschichten (oder Gedichte und so), weniger aber Gedanken. Diese bleiben weiterhin das Metier der Stammtische und Philosophen und wir wollen doch nicht diesen Berufsgruppen die Lebensgrundlage entziehen.

Aber dennoch und ausnahmsweise und der guten Sache wegen durften die Hüterinnen und Hüter des Narrativen im Abstrakten wildern. So etwa Thomas Glavinic, dessen Gedanke lautete: „Man soll nicht alles glauben, was man denkt.“ Unschwer erkennt man, dass hier vernünftelt wird, was für sich genommen ja legitim ist und ganz in Ordnung geht. Es spießt sich erst, wenn man an die bildliche Umsetzung denkt, die ja die selbstgewählte Aufgabe der Lipuš’schen Intervention darstellen sollte. Warum nämlich, so muss man sich fragen, gibt es von Kants „Kritik der reinen Vernunft“, von Hegels „Phänomenologie des Geistes“ (und so weiter) keine illustrierten Ausgaben? Entzieht sich das „Ding an sich“ der Darstellbarkeit? Wie sieht das „an und für sich“ aus? Hat es einen Leberfleck? Lächelt es? Arno Geiger liefert mit seinem Gedanken auch gleich ein weiteres Stückchen Hegel: „So schleicht die Geschichte ihrem Ende zu.“ Kant wiederum klingt in Sabine Scholls Gedanken, der da lautet: „Der Verstand gehört zum Haus.“ – Oder funkt hier Heideggers Seinshüttendenken dazwischen?

Wie dem auch sei, das Ausgangsmaterial für Marko Lipuš’ Cartoons ist alles andere als konkret. Und genau hier beginn sein kluges Spiel, das mit Ironie, einer Portion Sarkasmus und den Möglichkeiten der fotografischen Montagetechnik das Abstrakte konkretisiert und in diesem Prozess unweigerlich eine Auslegung, Festlegung, eine Interpretation liefert. Sabine Scholls „Gedanke“ etwa wird zum Parlamentsgebäude – von wegen Verstand! –, dessen Mittelrisalit eine Hundehütte mit angekettetem Hundsvieh bildet. Ein links zu sehendes Podest trägt einen Knochen als Säule, also doch wieder ganz Hegel, der so treffend wie apodiktisch-kantig schrieb: „Der Geist ist ein Knochen.“ – Dies den Herren des Hohen Hauses ins Logbuch geschrieben. Arno Geigers „Gedanke“ konkretisiert sich durch ein Auto mit überdimensioniertem Auspuff, einer Variante von Munchs „Schrei“ auf einer Landstraße und schließlich einem großmütterlichen Wecker ohne Zeiger. Was sagt uns das? Der Begriff „schleichen“ wird konterkariert durch ein Sinnbild des Geschwindigkeitsrausches, der Schrei erinnert an Schillers Satz „Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht“, um schließlich als dysfunktionaler Wecker in Hegels Satz von der „schlechten Unendlichkeit“ zu münden. Dass Lipuš damit der Idee einer sinnbeladenen Stoßrichtung menschlicher Geschichte eine klare Absage erteilt, ohne sie ins pathetische Gewand der Desillusionierung zu kleiden, macht diesen Cartoon so sympathisch.

Freilich, die Illustrationen könnten auch ganz anders aussehen. Das unterscheidet sie von Cartoons, die Romanen entspringen, etwa Prousts „Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit“ oder jene Serie von Comics, die die Kriminalromane von Leo Malet zum Inhalt hat. Diese zufälligen Beispiele, deren Pariser Fokus ebenfalls nichts als Zufall sein muss, zeigen, dass es bei Lipuš’ Fotocartoons um etwas anderes geht als darum, Anschaulichkeit herzustellen.

Wie anders seine Bilder funktionieren, kann erkennen, wer das Experiment unternimmt, sie nicht als Illustrationen, sondern umgekehrt die jeweiligen „Gedanken“ als Ekphrasis der Bilder zu begreifen. Bleiben wir vielleicht gleich bei der Konkretisierung von Scholls „Gedanken“ und kehren die Chronologie um. So könnte der Satz zu Lipuš’ Bild mit gleichem Recht lauten: „Uns alle behütet der Geist.“ Oder etwa wie die folgende Definition Foucaults, der irgendwo schreibt: „Kritik ist die Kunst, sich nicht so regieren zu lassen.“ Tausend andere Formulierungen sind ebenso zulässig und ebenso schlüssig, sobald die Beziehung zwischen Bild und Schrift hergestellt wird.

Mit einem Mal aber wurde aus dem Konkreten des Bildes das Abstrakte (oder Allgemeine) wie andersrum aus dem abstrakten Gedanken die Konkretion. – Und man darf nicht glauben, dass dieses Gedankenexperiment im Betrachten des Ganzen von Bild und Schrift nicht ebenso präsent wäre wie die Umkehrung. Unablässig verteilen sich die Rollen neu und produzieren ein Gebilde, das nicht zur Ruhe kommt.

Solches Wechselspiel trägt Lipuš darüber hinaus noch in die Idee der Autorschaft hinein: Links von jedem seiner Fotocartoons befand sich ein eigenes Fenster, das den Namen des Schriftstellers und jenen des Cartoonisten nannte. Von beiden Namen liefen Pfeile auf eine winkende Person, bestehend aus Mantel, Hut und winkender Hand. Wen zeigt diese Montage? Den Urheber des Bildes oder jenen des Textes? Mal diesen, mal jenen? Keinen von beiden? Stecken sie unter einer Decke, unter einem Mantel?

Unversehens finden wir uns im Bereich jener „Unentscheidbarkeit“ wieder, die Derrida in immer neuen Anläufen auf Tausenden von Seiten zu verdeutlichen versuchte, und die als Urteilsenthaltung, als epochê, schon der pyrrhonischen Skepsis bekannt war.

Den Fotokünstler Marko Lipuš mag immerhin eine andere Behauptung Derridas trösten, die da lautet: „Das letzte Wort haben immer noch die Bilder.“ – Doch auch das ist ja wieder ein Satz.

ON IMAGES AND TEXTS – ON TEXTS AND IMAGES

— Meinhard Rauchensteiner

Prima la musica, poi le parole, we say glibly, and as long as we’re not talking about Schubert’s Erlkönig, we tend to believe it. Forget about the Ode to Joy, but the overall question remains: How does it work when words are set to music? The expression itself implies that the text is there first and the musica comes later. Well, perhaps chronologically. But is chronology relevant to a work of art? Now that even plagiarism has been elevated to an art form that meets with almost hysterical acclaim, earning good money for today’s publishers and Hegemanns, who still cares about that old-fashioned question of which came first, the chicken or the egg?

However, in places other than Berlin they may be less desperate to throw the baby out with the bathwater, and perhaps we can put aside our flippant indifference for a moment while we take a look at Marko Lipuš’s photo cartoons, which are the actual subject of this discussion, as I may have forgotten to mention at the beginning (but so what?).

Between March and October 2007, these photo cartoons – there are something like a considerable number of them – appeared week by week in “Album,” the weekend supplement of the Austrian newspaper Der Standard. They originated when the author approached a string of writers with the idea that each of them should formulate a “thought,” based on which he would then create some images. Logically enough, the resulting intervention was surtitled The Thought. In the singular, mind you. Now this in itself is highly intriguing given that writers produce stories (or poems and the like) rather than thoughts, which are the prerogative of armchair politicians and philosophers, and it wouldn’t be fair to deprive those occupational groups of their livelihood.

Nevertheless – but just this once, because it’s for a good cause – the keepers of the narrative were permitted to encroach on the territory of abstraction. Take, for example, Thomas Glavinic’s thought, “Don’t believe everything you think.” Clearly a very subtle distinction is being made here, which in itself is perfectly legitimate and no problem at all. But when it comes to the visual interpretation – and that is, after all, the self-imposed task of Lipuš’s intervention – things start to get dicey. You have to wonder why there are no illustrated editions of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, and so on. Does the thing-in-itself defy representability? What does the “in and for itself” look like? Does it have a beauty mark? Does it smile? With his thought Arno Geiger gives us another chunk of Hegel: “This is how history is crawling towards its end.” Kant, on the other hand, resonates in Sabine Scholl’s thought, “Reason belongs to the house.” Or has Heidegger’s “Building Dwelling Thinking” sneaked in here?

Whatever – the source material for Lipuš’s cartoons is anything but concrete. And this is exactly where he begins his clever game in which irony, a dash of sarcasm and the possibilities offered by photomontage are used to concretize the abstract, inevitably supplying a definition and an interpretation in the process. For example, Scholl’s thought is transformed into the Austrian parliament – so much for reason! – and the building’s median risalit takes the shape of a doghouse, in front of which is a dog on a chain. Over on the left is a pedestal bearing a bone instead of a column. Once again we have Hegel, who wrote aptly and apodictically that “the spirit is a bone.” (Honorable gentlemen in parliament, take note.) Geiger’s thought is concretized into a car with an oversized exhaust pipe, followed by a variation on Munch’s The Scream on a country road, and finally a vintage alarm clock with missing hands. What do they tell us? By evoking the thrill of speed, the car challenges the word “crawling.” The scream recalls Schiller’s dictum that “the history of the world is the world’s court of justice,” and ends up as a dysfunctional alarm clock in Hegel’s notion of bad infinity. What makes this cartoon so engaging is that Lipuš refuses to clothe his rejection of the idea of a meaningful thrust of human history in the pathos of disillusionment.

The illustrations could have turned out differently, of course. That distinguishes them from cartoons derived from fiction, such as Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, or a comic book series based on Léo Malet’s detective novels. These random examples, whose Parisian setting may also be simply coincidental, show that Lipuš’s photo cartoons are not necessarily aimed at creating clarity.

We can see just how differently his images function if we conduct the following experiment: Instead of looking at the images as illustrations, we understand the individual thoughts as ekphrastic descriptions of the images. Let’s go back to the concretization of Scholl’s thought and reverse the chronology. The statement for Lipus’s image could just as easily have been “And the spirit protects us all.” Or, as Foucault wrote somewhere, “Critique is the art of how not to be governed like that.” A thousand other phrases would be just as acceptable and convincing once a relationship is established between image and text.

Yet the concrete image suddenly becomes abstract (or generalized), in the same way as the abstract thought becomes concrete. And it would be wrong to assume that this thought experiment in viewing the image and text as a whole would not be present just as the reverse. The constant redefinition of the roles creates a construct in flux.

Lipuš takes this interplay further, extending it to the idea of authorship: In each of his photo cartoons, there is a field on the left that includes the name of the writer and that of the cartoonist. From both of these names arrows point to a figure who is waving. The figure is made up of a coat, a hat, and a raised hand. Who is depicted in this montage, the author of the image or the author of the text? Now the former, now the latter? Neither one? Or are the two of them in cahoots?

Once again we abruptly find ourselves in the realm of that undecidability which Derrida needed thousands of pages to explain, and which goes all the way back to epoché (the suspension of judgment) in Pyrrhonian skepticism.

The photographic artist Marko Lipuš can seek consolation in Derrida’s assertion, “Images still have the last word.” But that too is just another statement.