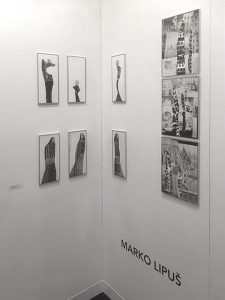

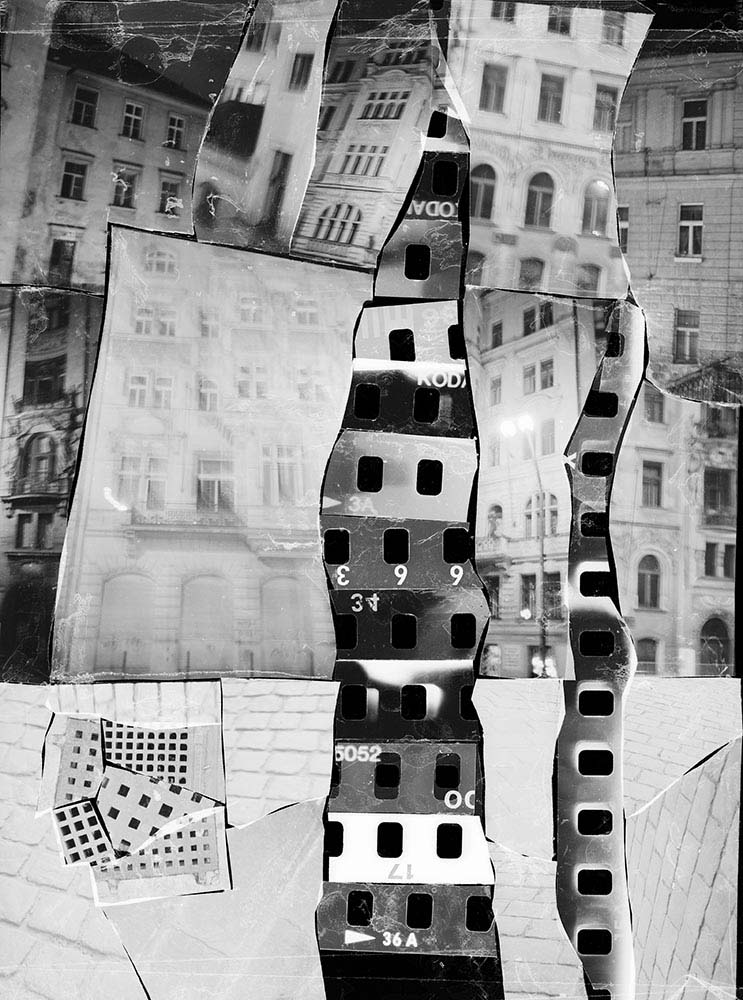

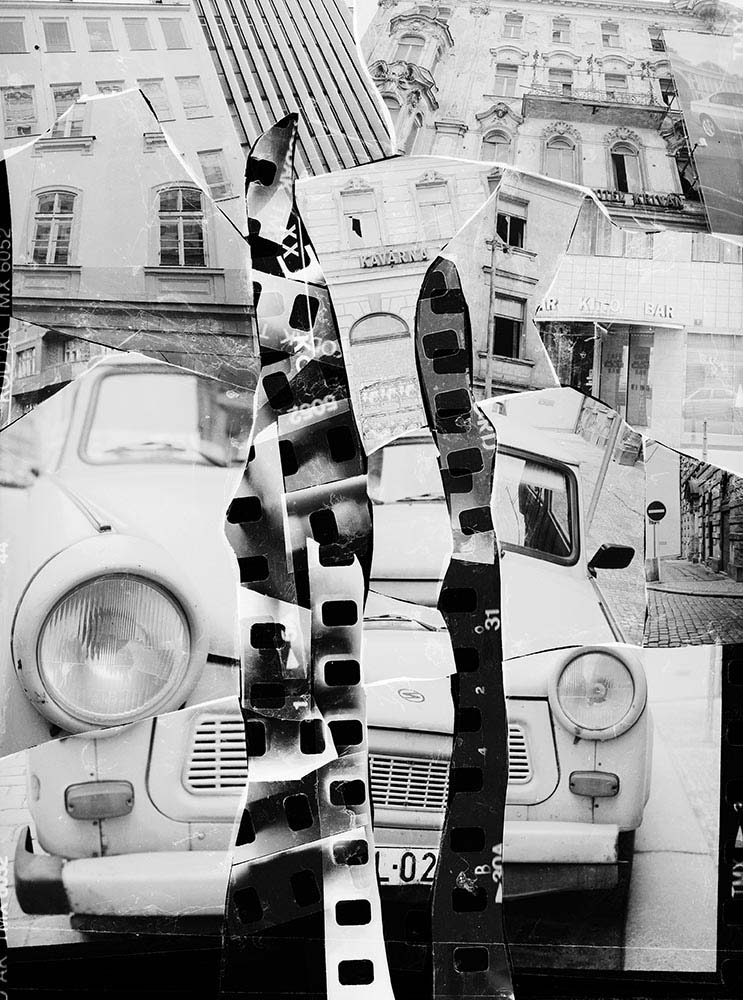

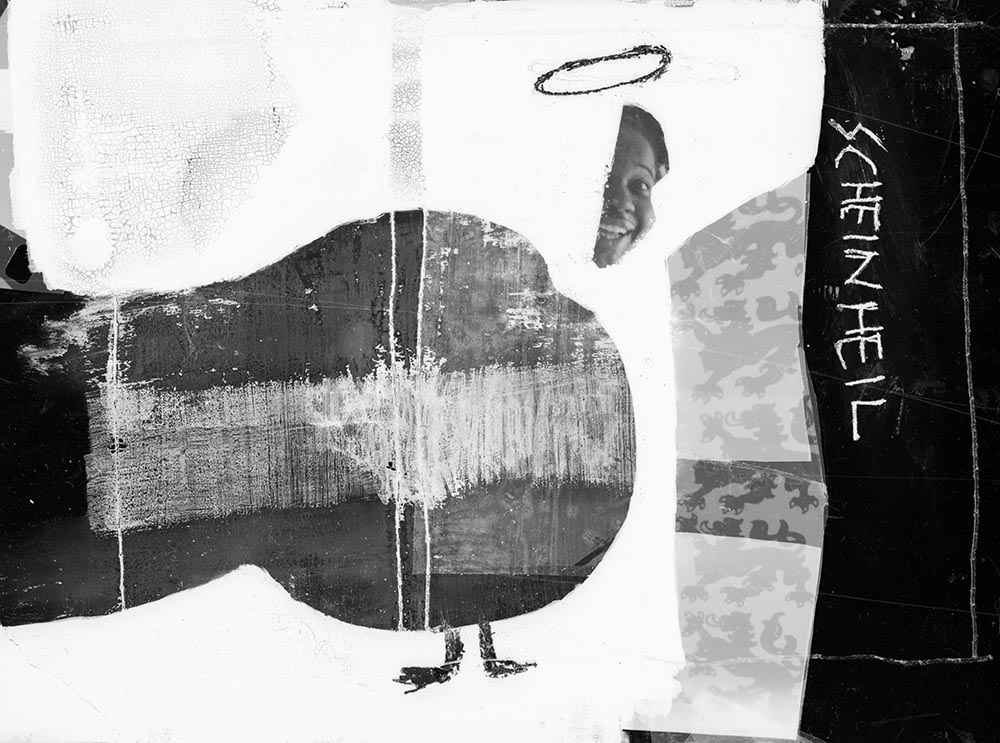

(1998 – 2001)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 15 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

30 x 30 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

30 x 30 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 26 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

26 x 35 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

26 x 35 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

26 x 35 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

26 x 35 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

35 x 175 cm | Silver gelatin print | Edition of 5 (+ 2 e.a.)

Bildband | Book

Softcover | 28 pages | Size: 37 x 29 cm | Edition: 350 copies

Drava Verlag, Austria, 2009 | ISBN: 978-3-85435-601-1

Book design by Doris Pesendorfer

Languages: German, English, Italian, Slovenian

Text by Michael Freund

MEHR AUSDRÜCKEN, ALS DIE KAMERA HEREINHOLEN KANN

— Michael Freund

Marko Lipuš und seine Herangehensweise an die künstlerische Fotografie

Am Anfang ist die Rebellion. Was normal, gegeben und immer schon da gewesen ist, gibt Anlass zum Zweifel. „Mein Ausgangspunkt ist, Normen nicht einfach zu übernehmen“, sagt Marko Lipuš. Andererseits, was ist die Alternative? „Es gibt ja nichts Neues, das ist klar.“

Das ist, zumindest scheinbar, das Problem der Fotografie, und es wird – so scheint es wiederum – jeden Tag um vielen Millionen Beispiele deutlicher. Ist nicht schon alles unter der Sonne tausendmal aufgenommen worden, und auch alles, wo keine Sonne hinkommt?

Aber ja. Aber nein. Denn das Gegenteil stimmt, rein formal gesehen, genauso: Nicht nur ist jeder Moment im Leben eines Kindes, eines Soldaten im Feld, eines Haustieres, jeder Urlaubstag, sind sogar alle Sonnenuntergänge und Blumen einmalig. Es kann auch das ewig Ähnliche zu etwas Neuem führen. Wer (sich) ein Bild macht, kann Unterschiedlichstes im Sinn haben. Wer das Bild nachher sieht, ebenfalls. Darum gibt es zwar Milliarden von Fotos – und trotzdem immer wieder neue Bilder. Wie etwa die von Lipuš, auch wenn er es selbst gar nicht zu glauben scheint.

Holen wir etwas weiter aus. Neben der Frage nach der Einmaligkeit bzw. Wiederholbarkeit steht der Akt des Fotografierens in einem weiteren Spannungsfeld: Das Resultat mag einerseits für sich sprechen. Es steht aber auch in einem außerbildlichen Kontext – ob das eine triviale, erklärende Bildunterschrift ist oder die Einbettung des Moments in konkrete Geschichte, wie sie Fotohistoriker verlangen und auch leisten.

Marko Lipuš ist kein Fotohistoriker, er sieht Fotografieren als künstlerischen Akt und – für ihn – als Notwendigkeit, als etwas Unmittelbares, ohne Umschweife und Umwege. „Das Visuelle alleine soll ausdrücken, bewegen, ansprechen“, sagt er. Das hätte meinen Onkel Leo gefreut, der sein Leben lang zu seinem Leidwesen mit Menschen zu tun gehabt hat, die ihre Kunstproduktion mit viel Brimborium garniert haben. Als er eines Tages im Fernsehen eine Künstlerin sah, die auf ihre erklärenden Texte neben ihren Bildern hinwies, sagte er: „Kunst mit Gebrauchsanweisung – das hab’ ich schon g’fressen!“

Auch Lipuš ist gegen „Beipackzettel“. Tatsächlich dient ja viel, was als „tolles Bild“ verkauft wird (im Wortsinn), praktischen Zwecken, sei es, um einen Text zu illustrieren, ein Produkt zu verkaufen oder eine gewisse technische Fertigkeit zu beweisen. Es ist mehr oder weniger gutes Handwerk. Marko Lipuš hat solche außerfotografischen Absichten nicht. Ihn interessieren die ästhetischen Gegebenheiten und ihre Veränderbarkeit. Alles andere mag gut gelingen, aber es ist keine Kunst. „Würde man“, fragt er rhetorisch, „einen Gebrauchstextverfasser in einem Literaturhaus vorlesen lassen?“ (Da regen sich bei mir eine Erinnerung und ein Widerspruch: Enzensberger hat einmal geraten, Zugkursbücher zu lesen, sie seien zuverlässiger als Poesie. Ankunftszeiten, Deodorantwerbung oder Flugblätter von Spiritisten im Literaturhaus – warum nicht? Aber das ist ein anderes Kapitel. Bleiben wir bei den Bildern.)

Die ästhetischen Kriterien der Fotografie hat Lipuš studiert, in Wien, in Prag, in seiner Praxis seither. Er beherrscht sie, erst kürzlich haben die deutschsprachigen Feuilletons drei seiner Porträts von Robert Menasse abgedruckt. So weit, so stimmig. Aber „gute Fotos“ waren nicht sein Ziel, „Schönheit ist zu wenig“. Er will, dass man über das simple Verhältnis „Hier ein Foto gemacht, dort das Resultat angeschaut“ hinausgeht.

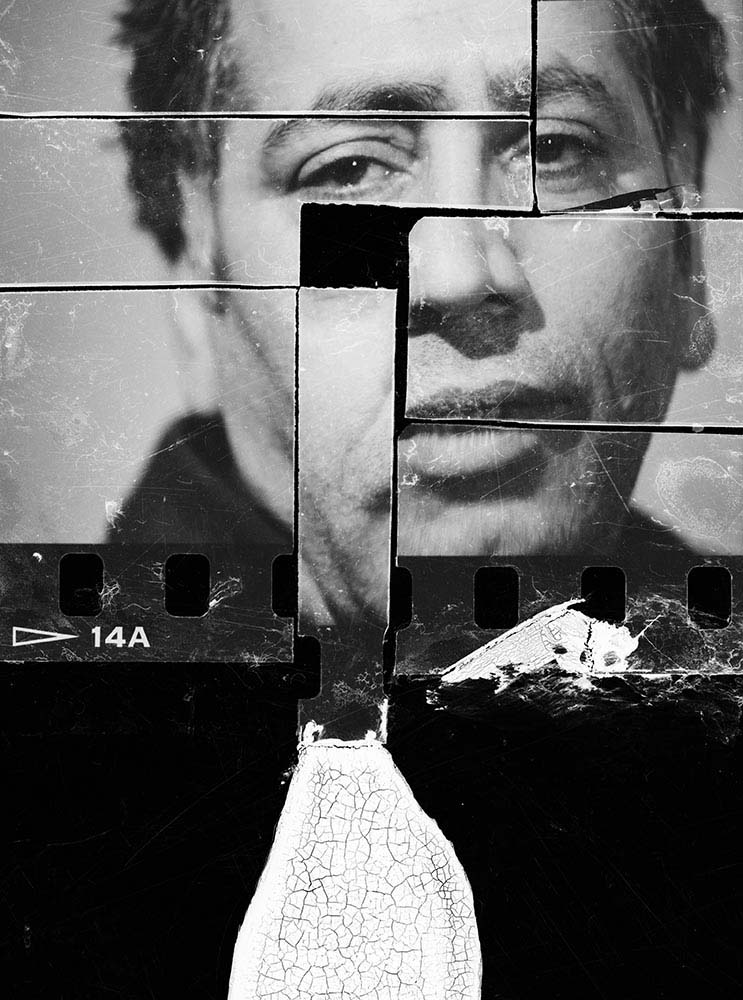

Bei der Suche nach Beispielen, wo diese Einfachheit, diese schnelle Rezeption durchbrochen wird, kommen wir auf die Cameraworks von David Hockney. Der Maler hat in den Achtzigerjahren mit Polaroids und Kleinbild gearbeitet, hat von Menschen, Wohnungen, Landschaften Dutzende sich überschneidender Aufnahmen gemacht und zu Collagen zusammengefügt. Dadurch bringt er die Zeit, die im Einzelbild verloren geht, wieder zurück. „Der Betrachter“, sagt Lipuš, „erfasst nicht alles auf einen Blick, sondern vielmehr Schritt für Schritt, und er setzt sich daraus das Bild zusammen“, sukzessive, so wie wir ja auch „in Wirklichkeit“ nicht alles auf einmal sehen.

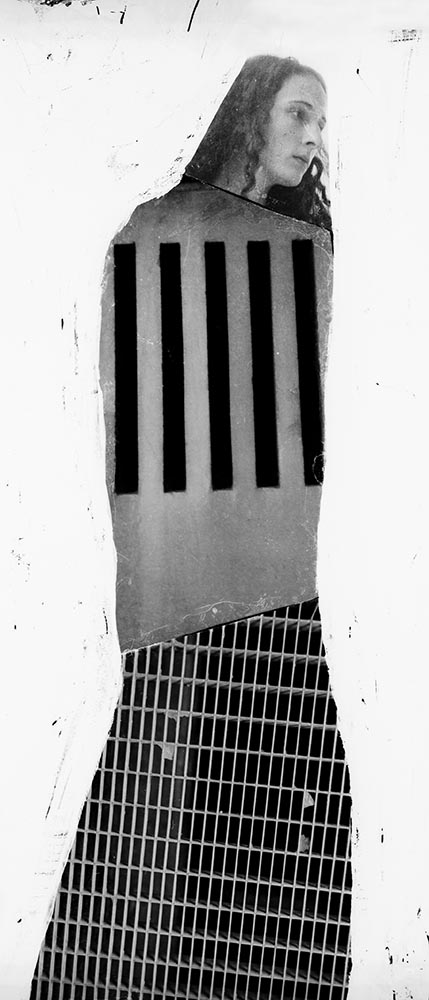

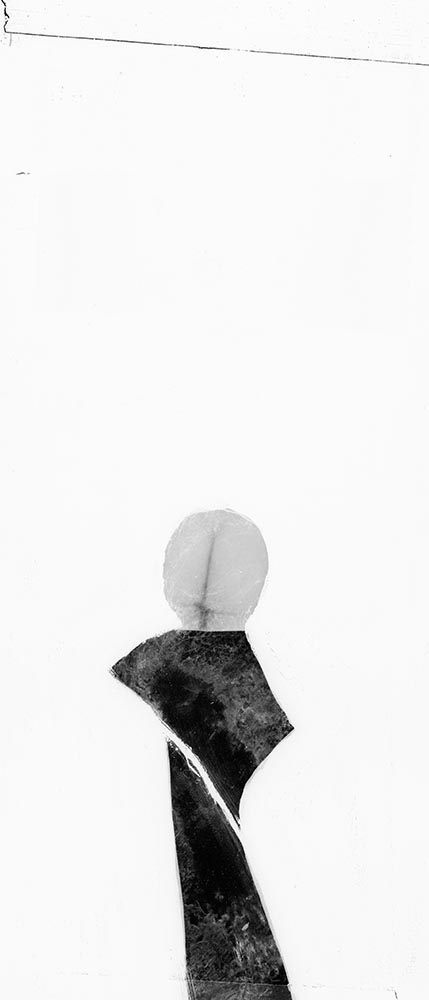

Lipuš aber geht einen entscheidenden Schritt weiter. Die Rebellion, mit der er das Gegebene hinterfragt, fängt beim Negativ an. Es ist ihm nicht sakrosankt und Beweismittel für Authentizität, vielmehr Rohmaterial für Eingriffe. Er übermalt, zerkratzt, collagiert das Ausgangsmaterial, vergrößert es zur weiteren Bearbeitung, er spielt mit der Emulsion, zerlegt Gesichter, verfremdet Klischees („Familie“). So wird ausgerechnet die als so naturalistisch angesehene Fotografie zu einem „Medium“, wie Stefan Gmünder einmal schrieb, „das Dinge zu leisten imstande ist, die anderen verwehrt bleiben“.

Als „Verfotografierungen“ bezeichnet ihr Urheber diese Eingriffe, und es klingt irgendwie brechtisch, als ob die Technik über diesen Umweg zu ihrem eigentlichen Sinn kommt. (Weil wir übrigens gerade von Hockney gesprochen haben: Er hat auch wieder einen Weg gefunden, sich den Normen seiner Kunst zu entziehen. Seit Neuestem produziert der akademisch ausgebildete Maler Bilder mithilfe der Software Brushes – auf seinem iPhone …)

Lipuš will mehr ausdrücken, als seine Kamera hereinholen kann. Die Überfrachtung des Fotografierens mit technischen Standards und kulturellen Erwartungen hat sich wie ein Grauschleier über die Bilderwelt gelegt. Doch manchen gelingt es, den Zustand zu erreichen, der laut Wissenschaftlern Neugeborenen eigen ist: Sie sehen die Welt heller, klarer. Vielleicht sieht Lipuš einfach mehr.

EXPRESSING MORE THAN WHAT THE CAMERA CAPTURES

— Michael Freund

Marko Lipuš and his approach to artistic photography

In the beginning there is rebellion. Everything, which has been accepted as normal, triggers doubt. All that has prevailed as the given standard has to be questioned. “My starting point is not to agree to the established norms without probing them,” states Marko Lipuš. On the other hand, what is the alternative? “There isn’t anything new that’s for sure too.”

This is at least at the first sight the inherent problem of the photography. By adding millions of millions of examples every day, everything under the sun and also everything beyond its reach has been photographed by now.

Yes and no. One may well take issues with that proclamation since, at least on a formal level, the position is valid too. Every moment in a child’s life, every moment of a solder in combat, of a pet, or each day of a vacation, even all sunsets and flowers are unique. The eternal sameness can lead to something new. Whoever takes a picture might have something specific on his mind; whoever looks at it might see something else. Even though there are billions of photos it is still possible to see new pictures. Like those created by Lipuš, although he seems to be suspicious of this possibility.

Let me elaborate further. Beside the inquiry about the uniqueness or repetitiousness of photography there is an additional area of tension. Even if the result might not need a spokesperson there is also a context outside the picture. Whether this is just a trivial, explanatory signature or whether this means the embedding of a moment into time as required and executed by historians of photography.

Marko Lipuš is not a historian of photography. He defines photography as a creative act that is essential and exceptionally straightforward without any diversions and deviations. In his opinion “The image alone shall communicate, stir and address”. My uncle Leo would have been delighted to hear that. His entire life he had to deal with people who, to his great chagrin, were adorning their art work with a lot of mumbo-jumbo. Once, as he was listening to an artist on a TV show who called attention to the explanatory texts below her art work, he grumbled “Art that comes with operating instructions gives me the willies.”

Lipuš too dislikes prescription leaflets. Very often indeed their purpose is to sell (in literal sense) a “great picture”. They opportune purpose is to illustrate a picture, to advertise a product or to prove a certain set of technical skills. They are more or less a display of good craftsmanship. Marko Lipuš does not have any of those intentions. He is interested in aesthetical particulars and how they can be changed. Anything else might sound very good but has nothing to do with art. “Would you invite”, he rhetorically inquires, “a writer of manuals to give a public reading at a writer’s event”? (However, I do recall one incident that raises some objections: Enzensberger advised to read train schedules since they are more reliable than poetry. Arrival times, advertisement for deodorants or leaflets written by spiritists – why not? But this is an entire different chapter. Let us stay with the pictures).

Lipuš studied the aesthetical criteria’s of photography in Vienna, in Prague, and has since done so in his everyday work. He does master these very well since just recently a major German newspaper published three of his portraits of Robert Menasse. But “good photos” were never his intention. “Beauty is not enough”. He requires more than the simple correlation of “taking a picture here and exhibiting the results elsewhere.“

Searching for examples that go beyond the straightforward and quick reception, we might turn to the Cameraworks by David Hockney. The painter worked during the eighties with Polaroid and 35 mm film. He made dozens of photo synthesis of one subject such as people, apartments, and landscapes; he arranged them as patchworks to make a composite image. This procedure allowed him to bring the aspect of time back into the photo, a dimension that disappears in a single take. “The viewer”, so Lipuš, “does not observe everything at once but rather examines step by step until he assembles gradually the entire picture, since we also don’t see “in actuality” everything at one glance.”

However, Lipuš takes a crucial step beyond that. The rebellion with which he challenges the conventional norms begins with the negative. He employs the negative as a raw material for various manipulations and not as a sacred foundation that proofs the authenticity. He paints over, scratches, and makes collages out the starting material. He zooms up for further processing. He plays with emulsion, segmented faces, and undermines clichés (such as family). Due to this process a photo usually viewed in a naturalistic fashion becomes a medium itself that according to Stefan Gműnder “is capable of doing things which others are not able to”.

The creator of these manipulations calls them “Verfotografierungen / re-photographs”. This echoes in a way Brecht, it sounds as if the technique arrived through this detour at its original purpose. (Since we have mentioned Hockney: In the meantime he has found another approach to challenge the established norms of his art. Recently the academically trained painter started to produce pictures with the software “Brushes” on his IPhone…).

Lipuš wants to express more than the camera is capable of recapturing. The photography has been taken over by technical standards and by cultural expectations. As a result, the world of images appears to be in a haze. But sometimes it is possible to see the world as a newborn does who, according to scientists, sees the world brighter, sharper. Maybe Lipuš does see more.